Thursday, September 29, 2011

Do I Annoy Because I'm a Jerk, Or Am I a Jerk Because I Annoy You?

Socrates has a reputation of being a bit of a jerk. The following robot reenactment of one of his dialogues does little to dispel this reputation:

Monday, September 26, 2011

Paper #1 Guidelines

(Want tips on writing a philosophy essay? Check out here and here!)

New Due Date: at the beginning of class on Friday, October 14th, 2011

Worth: 50 points (5% of final grade)

Assignment: Write an argumentative essay on external world skepticism: the claim that we do not know anything about the physical world beyond our immediate sense experiences. In particular, choose one of the topics below. Papers must be typed, and must be between 500-800 words long. Write down the word count on the first page of the paper.

Possible Paper Topics

1. Criticize skepticism of the external world. Describe what you take to be the best argument for external-world skepticism. Then evaluate this argument. Exactly how is this argument bad? Be specific: what is/are its flaw(s)? How can we avoid giving in to the skeptic’s arguments that we don’t know anything about the world?

[NOTE: For this option, you don’t have to present a positive argument for the existence of the external world. Just explain why the skeptical argument you focus on is bad.]

2. Tell me why you’re not a skeptic: Present and defend an argument for the claim that we can know that there is an external world beyond our sense experiences. Be sure to consider and respond to objections to your argument that a skeptic would likely offer.

3. Defend external-world skepticism. Present an argument for external-world skepticism. Then consider and respond to objections to this argument. Pay special attention to your conception of knowledge: defend the conditions you believe are required for knowledge.

4. Explain and evaluate Nick Bostrom’s argument in “Do We Live in a Computer Simulation?”Do you think Bostrom makes a good case for external-world skepticism? Why or why not? Be sure to fully explain your evaluation of his argument, and defend your opinion.

5. Write something else on skepticism. (Sean must approve this topic by Wednesday, October 5th.)

New Due Date: at the beginning of class on Friday, October 14th, 2011

Worth: 50 points (5% of final grade)

Assignment: Write an argumentative essay on external world skepticism: the claim that we do not know anything about the physical world beyond our immediate sense experiences. In particular, choose one of the topics below. Papers must be typed, and must be between 500-800 words long. Write down the word count on the first page of the paper.

Possible Paper Topics

1. Criticize skepticism of the external world. Describe what you take to be the best argument for external-world skepticism. Then evaluate this argument. Exactly how is this argument bad? Be specific: what is/are its flaw(s)? How can we avoid giving in to the skeptic’s arguments that we don’t know anything about the world?

[NOTE: For this option, you don’t have to present a positive argument for the existence of the external world. Just explain why the skeptical argument you focus on is bad.]

2. Tell me why you’re not a skeptic: Present and defend an argument for the claim that we can know that there is an external world beyond our sense experiences. Be sure to consider and respond to objections to your argument that a skeptic would likely offer.

3. Defend external-world skepticism. Present an argument for external-world skepticism. Then consider and respond to objections to this argument. Pay special attention to your conception of knowledge: defend the conditions you believe are required for knowledge.

4. Explain and evaluate Nick Bostrom’s argument in “Do We Live in a Computer Simulation?”Do you think Bostrom makes a good case for external-world skepticism? Why or why not? Be sure to fully explain your evaluation of his argument, and defend your opinion.

5. Write something else on skepticism. (Sean must approve this topic by Wednesday, October 5th.)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

knowledge,

logistics,

more cats? calm down sean,

skepticism

Friday, September 23, 2011

An Argument's Support

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure (or support) of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of the term. If you've been struggling to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Evaluating Deductive Arguments

Here are the answers to the handout on evaluating deductive arguments that we did as group work in class.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

P1- true

P2- true

support- valid

overall- sound

2) All email forwards are annoying.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)3) All males in this class are humans.

P2- true

structure- valid (the premises establish that some email forwards are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those forwards] are false)

overall- unsound (bad first premise)

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

P1- true4) No humans are amphibians.

P2- true

support- invalid (the premises only tell us that males and females both belong to the humans group; we don't know enough about the relationship between males and females from this)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

P1- true5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

structure- valid (the premises say that frogs belong to a group that humans can't belong to, so it follows that no frogs are humans)

overall- sound

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

support- invalid (we don't know anything about the relationship between mammals and winged creatures just from the fact that bats belong to each group)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) Oprah Winfrey is a person.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

support- valid (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- unsound (bad 2nd premise)

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

P1- true8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- true (you might not have directly seen anyone eat tacos, but you have a lot of indirect evidence... with all the Taco Bells, Don Pablos, etc., surely lots of people ate tacos yesterday)

support- invalid (the 2nd premise only says some ate tacos; Oprah could be one of the people who didn't)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- invalid (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

structure- valid (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- unsound (bad 3rd premise)

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)12) All students in here are humans.

P2- true

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise and structure)

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

P1- true13) (from Stephen Colbert)

P2- true!

support- invalid (the premises state a strong statistical generalization over a large population, and the conclusion claims that this generalization holds for a much smaller portion of that population; even though it's likely that most students in here are, in fact, shorter than 7 feet tall, it nevertheless could be true that the humans in here are a statistical anomaly)

overall- unsound (bad support)

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

support- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)15) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad premises and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)16) If there is no God, then life is meaningless.

P2- true

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise)

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

P1- questionable (that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

P2- questionable (again, that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

support- valid (the same structure as argument #15)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

An Expert for Every Cause

Looking for links on arguments from authority? This is your post! First, here's an interesting article on a great question: How are those of us who aren't experts supposed to figure out the truth about stuff that requires expertise?

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies (this article was originally published in the Chronicle of Higher Education).

We should judge experts who are into making predictions on how accurate their predictions turn out. Well, most experts are really bad at predicting, and have the same biases as non-experts.

It's important to check whether the person making an appeal to authority really knows who the authority is. That's why we should beware of claims that begin with "Studies show..."

And here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies (this article was originally published in the Chronicle of Higher Education).

We should judge experts who are into making predictions on how accurate their predictions turn out. Well, most experts are really bad at predicting, and have the same biases as non-experts.

It's important to check whether the person making an appeal to authority really knows who the authority is. That's why we should beware of claims that begin with "Studies show..."

And here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

Labels:

arguments,

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

links,

videos

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Non-Deductive Arguments

Here are the answers to the group work we did in class on args by example, args by analogy, args from authority, and args about causes. Conclusions are in bold.

1. That Honus Wagner baseball card shouldn’t be that valuable. After all, it’s made out of cardboard, and cardboard boxes at Pathmark are super cheap.

10. In 2006, Philadelphia had the highest murder rate in its history. That same year, Mark Wahlberg spent a lot of time in Philadelphia while filming the movie Invincible. Thus, Mark Wahlberg’s presence in Philly probably led to such a high murder rate.

10. In 2006, Philadelphia had the highest murder rate in its history. That same year, Mark Wahlberg spent a lot of time in Philadelphia while filming the movie Invincible. Thus, Mark Wahlberg’s presence in Philly probably led to such a high murder rate.

1. That Honus Wagner baseball card shouldn’t be that valuable. After all, it’s made out of cardboard, and cardboard boxes at Pathmark are super cheap.

Analogy2. China, India, Brazil, Nigeria, and Russia are all countries with populations greater than 100 million citizens. Hence, most countries have populations larger than 100 million citizens.

Bad - Material isn't always a relevant similarity to draw a conclusion about value: baseball cards are typically valued for their rarity, not what they're made of.

Example3. In a recent study, 100% of those who took a new birth control pill didn’t get pregnant. Only males participated in the study. Thus, the birth control pill must be very effective.

Bad - 5 countries out of about 200 total nations is too small a sample. Also, the examples are cherry-picked, and so they're unrepresentative.

Cause4. Oasis sounds just like The Beatles. We all know that The Beatles were one of the most influential rock bands ever. So Oasis must be one of the most influential bands, too.

Bad - A better explanation of the correlation between taking the pill and not getting pregnant is that males don't get pregnant.

Analogy5. Abortion is morally acceptable because renowned linguist Noam Chomsky has defended the practice of abortion, and he’s pretty smart.

Bad - A similar sound isn't a relevant enough similarity regarding whether a band is influential.

Authority6. Most people say the money it costs to go to law school is worth it, because lawyers earn a lot of money. So, since doctors also earn a lot, med school costs must be worth it, too.

Bad - Chomsky's expertise (linguistics) isn't relevant to the topic of abortion.

(Chomsky explains his view on abortion in the video to the right.)

Analogy7. My friend knows me better than anyone else, and he says I’m a decent guy. Therefore, I must be a decent guy.

Pretty Good - The similarity (average money earned per profession) is relevant to whether med school is financially worth it. Assuming one thinks a large up-front investment is worth an even larger salary in the future, this arg is good.

Authority8. My sis usually keeps her car windows rolled down, though she always rolls them up right before it rains. Her car must be magical, then: rolling up her windows causes it to rain.

Bad - Yes, my friend is a relevant expert, but he's likely to be biased in favor of me since he is my friend.

Cause9. I expect this new pair of cheap, black shoes to last me about 9 months, since the last pair of cheap, black shoes I bought wound up lasting about 9 months until I wore them out.

Bad - This is reversed! The rain probably causes her to roll up her window, not the other way around.

Analogy

Pretty Good - More information would be better--for instance, it's not clear whether the two pairs of shoes are the same brand and model--but the similarities (same owner, cheapness) are relevant to the conclusion of how long the shoes will last.

10. In 2006, Philadelphia had the highest murder rate in its history. That same year, Mark Wahlberg spent a lot of time in Philadelphia while filming the movie Invincible. Thus, Mark Wahlberg’s presence in Philly probably led to such a high murder rate.

10. In 2006, Philadelphia had the highest murder rate in its history. That same year, Mark Wahlberg spent a lot of time in Philadelphia while filming the movie Invincible. Thus, Mark Wahlberg’s presence in Philly probably led to such a high murder rate.Cause

Bad - This is most likely a coincidental correlation between Wahlberg's stay in town and the high murder rate.

Monday, September 19, 2011

Penguin Digestion Experts? You Bet!

So you didn't believe me when I said that there are experts on the subject of penguin digestion? Oh, you did? Fine, well, I'll prove it to you, anyway. Here are some academic articles on the topic:

Perhaps my favorite, though, is the following:

- Adjustments of gastric pH, motility and temperature during long-term preservation of stomach contents in free-ranging incubating king penguins from a 2004 issue of Journal of Experimental Biology

- Feeding Behavior of Free-Ranging King Penguins (Aptenodytes Patagonicus) from a 1994 issue of Ecology

Perhaps my favorite, though, is the following:

- Pressures produced when penguins pooh—calculations on avian defaecation from a 2003 issue of Polar Biology

Labels:

arguments,

as discussed in class,

links,

videos

Friday, September 16, 2011

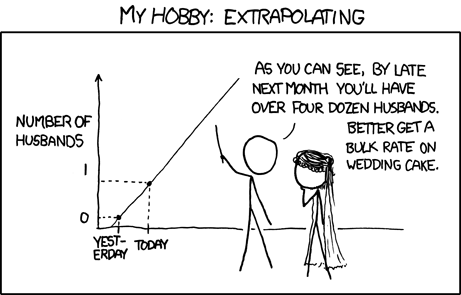

Here's yet another stick-figure comic (for those keeping track, that's four total on the blog so far). This one's about correlation.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Our Inductive Minds

Here are some more thoughtful links on inductive reasoning (or arguments by example).

- What are the benefits and dangers of generalizations?

- What makes stereotyping illogical?

- Beware: we often make snap judgments before thinking through things. Then when we do think through things, we just wind up rationalizing our snap judgments.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Arguments by Example

Here are a few dumb things about arguments by example (also called inductive arguments, talked about in the book chapter titled "Generalizations"). First, a video of comedian Lewis Black describing his failure to learn from experience every year around Halloween:

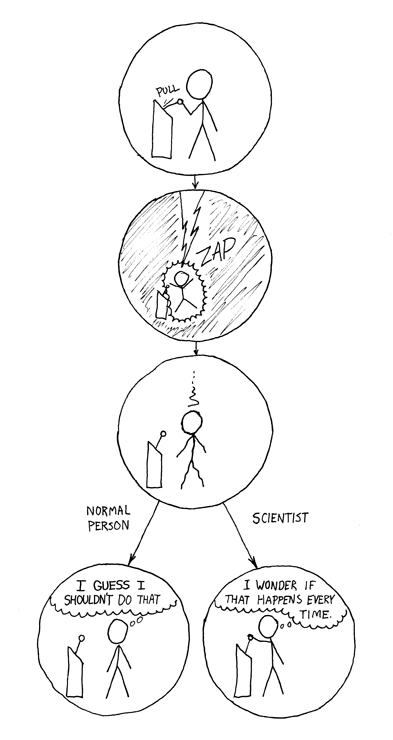

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Labels:

arguments,

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

links,

videos

Friday, September 9, 2011

That Beyoncé Video WAS Great...

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

links,

videos

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Howard Sure Is a Duck

Howard the Duck is my favorite synecdoche for the 80's:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Monday, September 5, 2011

Philosophers In Their Own Words

Photographer Steve Pyke has a cool series of portraits of philosophers. Many of the philosophers also provide a short explanation of their understanding of what it is they do. Here are a few of my favorites:

Delia Graff Fara:

Delia Graff Fara:

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Delia Graff Fara:

Delia Graff Fara: "By doing philosophy we can discover eternal and mind independent truths about the ’real’ nature of the world by investigating our own conceptions of it, and by subjecting our most commonly or firmly held beliefs to what would otherwise be perversely strict scrutiny."

"Philosophy is the strangest of subjects: it aims at rigour and yet is unable to establish any results; it attempts to deal with the most profound questions and yet constantly finds itself preoccupied with the trivialities of language; and it claims to be of great relevance to rational enquiry and the conduct of our life and yet is almost completely ignored. But perhaps what is strangest of all is the passion and intensity with which it is pursued by those who have fallen in its grip."

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):"Given the amount of suffering and injustice in the world, I flip-flop between thinking that doing philosophy is a complete luxury and that it is an absolute necessity. The idea that it is something in between strikes me as a dodge. So I do it in the hope that it is a contribution, and with the fear that I’m just being self-indulgent. I suppose these are the moral risks life is made of."

Friday, September 2, 2011

Philosophy: The Annoying 3-Year-Old

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Kit Fine

Kit Fine